Twelve nights ago, before the Timberwolves’ four-game road losing streak, the whiteboard in the team’s locker room was split into two rectangular sectionals. The left-most portion read “D”, the right side “O.”

The top-most portion of the left was riddled with doodles, presumably drawn by Tom Thibodeau, illustrating what appears to be playsets of that night’s opponent, Charlotte. Below, there was a subsection labeled “PnR.” Here, there were descriptions of what to do against “2×4” (a shooting guard and power forward pick-and-roll), “3×4” (small forward-power forward), “2×5” (shooting guard-center) and so forth. Only one position was defined by name: “Walker.”

Half of the board was filled with counters to ball-screen actions that would involve Charlotte’s point guard Kemba Walker. Demarcations for adjustments dependent on where the screen is set for Walker, what direction he is moving and how the coverage should differentiate accordingly.

It was the most elaborate scheming I have ever seen the board have.

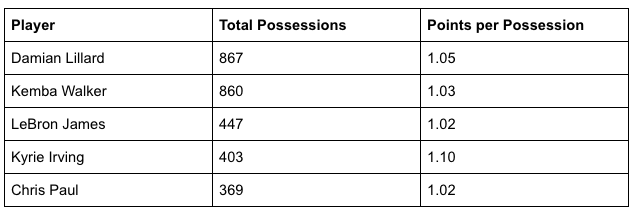

Why the elaboration? Well, that answer is twopence. First, Walker is one of the league’s premier pick-and-roll instigators, empowered by a team-wide infrastructure that leans into their star’s greatest strength. Only Damian Lillard ran more pick-and-rolls than Walker last season, per Synergy Sports. Further, Walker was one of only five players to average over one point per possession in those actions.

That’s enough to explain the presence of Walker’s name on the board. The quantity of times it pops up, however, speaks to something else: a diversity of the ways in which the Wolves can now, with Robert Covington, defend Walker (or anyone else) in these actions.

When Healthy, Robert Covington Has Changed How The Wolves Defend

Just as Walker’s presence allows Charlotte to lean into an offensive ball-screen attack, Covington is making it possible to lean — literally — into the way the Wolves defend pick-and-rolls. Before the Jimmy Butler trade, the Wolves defense had begun to evolve a bit but they were only implementing defensive aggression on occasion.

Most frequently, the pre-Covington Wolves rested on their tattered defensive laurels of last season — “Drop Coverage.” Back then, when the opponent would line up for a high pick-and-roll, Karl-Anthony Towns would strap on on a metaphorical harness fully-equipped with a hook and toe rope that would attach at his tailbone. When high screens came, Thibodeau operated a crankshaft at the stanchion of the hoop, yanking Towns into the paint. This (“drop” or “blue”) coverage, was the defensive counter for the vast majority of the pick-and-roll attacks the Wolves faced.

But now, with Covington in tow, there is a greater diversity to the ways the Wolves counter-punch. Instead of the inherently reactive drop scheme, the Wolves have become increasingly proactive. Rather than attempting to simply slow or contain the action the opponent wants to run, they have had defensive successes through forcing the opponent to pivot midstream.

Defending Walker specifically is an example of the new diversification of defensive coverages. Last season, Dwight Howard would set his screens on Walker so high that the advantage of drop coverage — forcing an on-the-move midrange pull-up — was negated. Walker would just pull-up from 3.

As Towns backpedaled, Walker would drool. In 2017-18, Kemba shot 4.6 pull-up 3-point attempts per game and converted those looks at a 38.1 percent clip. The drop coverage allowed Walker to do what he wanted to do: fire away.

Covington’s presence has empowered Thibodeau to defend these actions — and Walker, specifically — with a different vigor. Sure, Kemba still got his from time-to-time but you gotta be blind to not see the difference here. I promise you this “weak” pick-and-roll coverage made Walker do whatever the opposite of drooling is.

It wasn’t just the pressure at the point-of-attack that led Walker to miss nine of his final 11 shots that game, it was the diversity of coverages.

The Straight Switch

A rare occurrence a season ago, KAT is allowed scamper; using quick, long strides to match Walker’s jitterbugging nature.

Showing High

Here, Towns is asked to “show high” so as to take away the pull-up. The risk is getting burnt in over-pursuit — which happens — but KAT is quick enough to self-correct when Walker doesn’t execute by going to the wrong side of the rim.

Drop Coverage

Towns bluffs the show by stomping out to beyond the arc — leading to Walker to pass up on the pull. By the time Walker is in attack mode, KAT has squared to drop — inviting Walker to meet him at the rim.

Second Party Switch Partnering

You’d be hard pressed to find anything like this on film last season because they didn’t have a player like Covington who could be a “switch partner” with just about anyone.

Through Covington’s positional versatility, the Wolves are essentially defending Walker with three players. Even though Covington’s man isn’t directly involved in the action, he involves himself. After recognizing the action, Covington directs Towns to stay home rather than switching onto Walker. He takes that on himself and forces Walker into a very difficult shot early in the shot clock. A win, regardless of the result.

Second Party Switch Partner Into Drop Coverage

Again in communication here, Towns and Covington are second party switch partners. This time, instead, Covington doesn’t blitz Walker — he drops. Even the normally sub-optimal counter of the drop can be beneficial if the ball-handler doesn’t know it’s coming.

This holistic whirlwind fired at Kemba throttled the Hornets and made the idea of a defensive glass ceiling a thought of yesteryear. But then they hit the road, without Covington.

On The Road, Everything Changed

“So he missed the Portland game and he missed five days (of team activities), so he sorta got out of rhythm,” Thibodeau said when asked what the hell exactly happened to the defense when the Wolves hit the road after that win against Charlotte. “And then we obviously didn’t play him the same amount of minutes we were playing him earlier.”

Covington did miss the first game of the road trip and, yes, the minutes were slashed by about 10 per night in losses two, three and four. In that perilous stretch, I think Thibodeau and Covington’s teammates realized they don’t only need Covington on the floor, they need all of Covington to find success.

With Covington completely out against Portland, the difference was glaring. There wasn’t only a hole in his slot but the other four gears locked up without Covington’s grease.

It’s hard to imagine these game-sealing high pick-and-rolls would have gone down the same way with Covington in the game.

If Covington is in the game in place of Jeff Teague, you’re probably not seeing that high screen defended with a pirouette, the way Teague did. But more realistically, Covington would have probably taken Derrick Rose’s spot.

As we saw against Charlotte, Covington and Towns are switch partners, so Covington could have painted over the screen Towns gets clobbered by in the paint by simply switching. With that, Covington is up with the big setting the screen (Jusuf Nurkic) and he’s contesting that shot. The Wolves lost that possession because Lillard took advantage of space that (a healthy) Covington could have negated.

The following possession is curtains because no one is really guarding anyone. Teague tries a Covington blitz impersonation, but that clearly hasn’t been communicated to Towns and Wiggins who also pursue the same spot. And that’s the game.

It was more of the same even with Covington back, two losses against Golden State and Sacramento. Whether it was the lingering effects on the injury or just Covington’s abbreviated stints, the Wolves were consistently a step behind the Warriors offense. And against Sacramento, the Wolves were blinded by the speed and consistently buried beneath screens that allowed the Kings to convert a franchise-record 19 shots from deep.

This is not the behavior the Wolves illustrated when Covington was healthy.

Running On Fumes, Getting Right

It’s easy to diagnose that the execution wasn’t there at any point on the road, with or without Covington. Pointing to the balky knee is one anecdote, but I don’t believe that’s it. If Covington is saying he is healthy enough to play, the expectation (in a vacuum), should be that he is making plays that drive winning. Sure, at 70-80 percent physical health, maybe the flying into passing lanes isn’t the expectation. But why did the other stuff fall apart? Where was the grease? Those are bigger questions. Ones that go beyond the Xs and Os.

Monday night Covington provided a non-injury related explanation for the slippage: his life is just a little crazy right now; for the road trip he was running of fumes. Like, real life shit.

“I know all the other stuff is, like, kind of out of my head now,” as he began to list the full-on lifestyle shifts that come with being traded to a team in the first year of a four year contract. “Trying to find a place (to live); get my family here; (buy) a car; moving. All that other stuff, trying to have all that stuff situated. I guess you could say that kind of put a strain on things.”

Being home helped him, that’s clear. Not only for Covington but the whole team is different at home. The 27-point victory Monday over Sacramento was their 12th home victory in 16 games at Target Center this season. They’re 2-12 on the road.

In that blowout, it didn’t really matter what was on the whiteboard. Sometimes what’s firing through the synapses is just as important as pick-and-roll coverages. What’s clear now, 16 games into the Covington era, is that how he performs in both of those aspects of the game — physically and mentally — steer this team as much as anyone on the team. When engaged in both, Covington has proven to be a weapon that changes everything. His coach certainly thinks so.

“Your body language is gonna give the other team either confidence or, if you have an intensity, like Robert on every play, that’s gonna say something too,” said Thibodeau. “It bothers him when someone scores. I think when you look at great defenders, that’s it.”