It was a matchup of two different branches from the same Mike Shanahan tree: Kevin Stefanksi and Gary Kubiak of the Minnesota Vikings versus Green Bay Packers head coach Matt LaFleur. On the one side, Stefanski and Kubiak’s old-school approach to the offense. On the other, a newer spin on the offense with more of an emphasis on shotgun formations and playing to the quarterback’s comfort zone in quick-game passing while still being rooted in the under-center, zone-running, play-action structure of the Shanahan offense.

Updated or not, the two offensive staffs should still be plenty familiar with each other’s systems. Their respective defensive staffs should be familiar with them, as well, given they practice against it in some capacity every day. And yet, when the two sides faced off last year, the Vikings’ passing offense capitulated, while the Packers’ passing offense was functional, if somewhat lackluster. Green Bay swept Minnesota with 21-16 and 23-10 victories.

The easy answer as to how this happened is that Aaron Rodgers is simply a better quarterback than Kirk Cousins. There is an argument to be made in that respect, and it is one I would make in subjectivity, but the numbers did not really bear that out last season. In each of the quarterbacks’ games not against each other, Cousins was significantly more productive.

In 13 non-Green Bay games (Cousins sat out Week 17), Cousins earned 1,003 passing DYAR (defense-adjusted yards above replacement) according to Football Outsiders, averaging about 77.15 DYAR per game. He was a well-above average, if not great, quarterback anytime the opposition was not wearing green and yellow. Rodgers, on the other hand, earned 759 passing DYAR, putting his 54.2 DYAR per game well below Cousins’ mark. Rodgers’ 54.2 non-Minnesota DYAR average was still plenty good in relation to the average quarterback, but pales when compared to Cousins’ non-Green Bay figures.

So despite Cousins being more productive on the whole and both coaching staffs being familiar with each others’ offenses, how exactly did Cousins and the Vikings implode, but Rodgers and the Packers did not? In the first installment of this two-part series, we will examine Rodgers vs. the Minnesota defense.

Rodgers and the Packers vs. Minnesota

In all honesty, the first half of the first matchup did a lot of the heavy lifting for Rodgers. Within that first half, at least more so than the other six quarters these two teams played, the Packers offense won the mini-game of forcing the Vikings in and out of two-high safety shells.

The Cliff Notes on one-high versus two-high defensive structures is that one-high safety structures are better for clogging the intermediate middle of the field and loading the box to fit the run, whereas two-high structures are generally more sound versus deep passes while surrendering support against the run. Additionally, with respect to the Packers offense specifically, two-high safety coverages often have better answers for deep over routes than one-high safety coverages do, which is a part of why the Vikings wanted to be in two-high.

Even Green Bay’s first play of the game was an exploitation of the very concept Minnesota’s two-high shells were supposed to be preventing.

[videopress bbxpFgfg]With the Packers in an under-center, balanced 12 personnel look and reduced wide receiver splits, this looks exactly like the outside/weak zone, play-action structure of every Shanahan-esque offense. A common route from these formations is the aforementioned deep over route, which is especially common when being run into the field. In this instance, Davante Adams threatens just that by bending his route stem from the painted numbers to the hash. In many coverages, it is the near safety’s (Harrison Smith, No. 22) job to nail down on this crosser and run with it. As soon as Smith tries to nail down on the crosser, Adams snaps back the other way on a corner route and is left wide open on the boundary for an easy explosive gain to kick things off for the Pack.

Over the next few series, the Packers had their way on the ground versus a healthy portion of two-high shells. When the Vikings tried adjusting early in the second quarter with a more aggressive one-high structure against one of the Packers’ under-center formations, Rodgers had ‘em right where he wanted ‘em. Hard play-action versus single-high structures is a green light to spread the deep safety thin and look for a deep pass to an outside wide receiver.

[videopress GwNRAldI]Naturally, that is just what the Packers aimed for. This play is essentially a three verticals play with the middle “vertical” bending early to stay under the single-high safety and potentially draw him down. The concept itself works just as intended, pulling the safety down and away from Adams booking it down the seam on the right side. While the Packers do not actually complete the pass, Adams does earn a defensive pass interference call levied against cornerback Xavier Rhodes, who really did not have an answer for Adams all game long.

Green Bay’s passing offense only started to unravel in the other six quarters of play when the offense shifted more towards operating out of the shotgun — without as much hard play-action — and leaning more on dropback passing than blending their run and pass game together. In turn, many of their deep attacks after those first two quarters, particularly in the second game, were not as deliberate as some of what they did in the first couple of quarters.

Much of that had to do with no wide receiver beyond Adams really having the tools to work themselves open on a consistent basis. Adams made up for 116 of Rodgers’ passing yards that day, which required 16 targets. Green Bay’s second leading receiver in that second game? Allen Lazard with nine targets, five catches and a whopping 45 yards. The intermediate and deep game was just dead, save for one or two plays from Adams over the middle. In fact, in the second meeting, Rodgers attempted nine passes beyond 10 yards to the outside portions of the field and failed to complete a single one of them.

The only one of those nine passes that did not hit the ground was an interception he threw to Anthony Harris, who did an excellent job of nailing down on a crosser from a split-safety alignment. Harris’ interception was exactly what the Vikings were trying to accomplish more of in the first game, but struggled to do because of how much better and more frequently the Packers were playing from under-center formations and forcing heavier boxes.

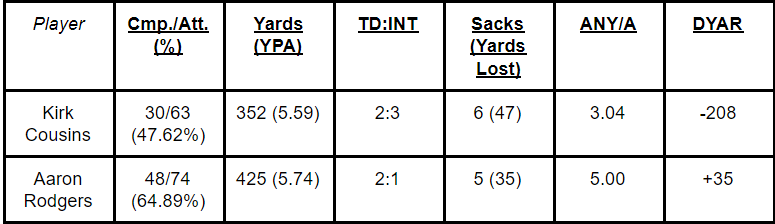

On the bright side for Rodgers, that interception was the only one he threw over the two games. He seldom put the ball at risk, which is certainly a theme for him of late. Moreover, Rodgers’ avoidance of negative plays in general is part of what separated him from Cousins in these two matchups. Rodgers gave up a sack once every 15.8 dropbacks and threw just the one interception on 79 total dropbacks, while Cousins surrendered a sack once every 11.5 dropbacks and threw an interception once every 23 dropbacks (out of a total of 69). Part of that is related to the respective pass protection each of them got, which we will hit during Cousins’ upcoming feature, but it does speak to Cousins’ implosion compared to Rodgers’ lukewarmness.

In all, the Packers’ offense skated by primarily because of one excellent half of exploitation of the Vikings’ two-high vs. one-high structures and Rodgers keeping his mistakes to a minimum. After those first two quarters of the first game, all the Packers offense really did was float along. With as spectacularly as the Vikings’ offense tried sinking itself, however, especially in the second game, merely staying afloat was all Rodgers needed to do for his offense.

The next installment of this series will walk through what went wrong with Cousins versus the Packers defense. By a number of measures, those two games were his worst of the season by far, and the film shows just how much the Packers did to keep Cousins down.