For almost a decade now, the Minnesota Vikings have waded through a morass of offensive line incompetency. Matt Kalil, T.J. Clemmings, Brandon Fusco, Jake Long, and Pat Elflein are just the tip of the o-line horror iceberg. It’s been a long time since the heyday of Phil Loadholt, John Sullivan, and Steve Hutchinson that propelled Adrian Peterson to an MVP award and dragged Christian Ponder to the playoffs.

What happened? How did we get here?

The Vikings seem entirely incapable of finding an NFL-caliber offensive line. They’ve been in the bottom six in PFF pass-blocking grade for three years running, and it’s not like they haven’t used draft capital to fix it.

In the last four years, they’ve used bottom-tier cap space on the position, opting instead to use valuable top-70 draft picks every single year. They’ve poured a ton of resources into meager progress at the position group. The reasons for this are worth looking into.

Youth

Each team is comprised of some portion of rookie contracts and some portion of veteran contracts. The Vikings have overwhelmingly tried to compile offensive lines on cheap deals. This is plenty costly when it comes to draft capital, and also ensures a youthful offensive line.

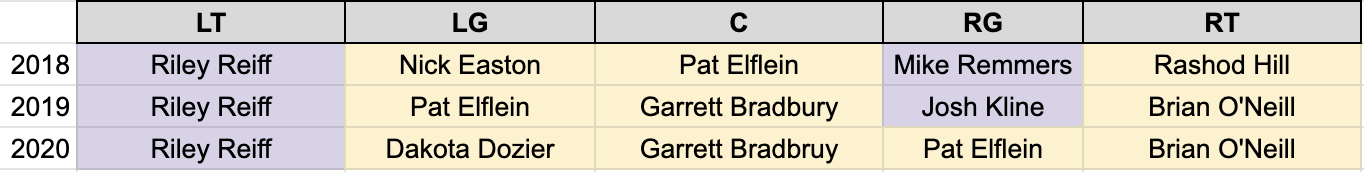

Below are the intended Week 1 starters in the Kirk Cousins era. In purple are market veteran contracts, in yellow are either rookie contracts or bargain bin deals.

The Vikings have always preferred to build through the draft rather than through free agency, so this isn’t a good or bad thing in a vacuum. Obviously, the results encourage a deeper look into that strategy. It might not be entirely on purpose that the Vikings are constantly trying to develop new young talent. Many of the large contracts on the Vikings’ books are extensions of successful draft picks, and they have not extended an o-lineman since they drafted since Brandon Fusco in 2014.

The result is a constant revolving door of young athletes in developmental years. Again, a young player who needs some coaching is not in and of itself a bad thing. In fact, it’s a good way to find value in the deep rounds of the draft. The Day 1-ready prospects all go for premium picks, but if you can wait a year, you can get just as good a player with a cheaper pick (or so the saying goes).

But there are deeper problems with the execution of that strategy.

Draft Philosophy

The Vikings have a somewhat unique approach to the draft. It produces more good than bad, but among that bad is the offensive line. So what’s wrong here? Even if they were better at evaluating talent, their approach puts them between a rock and a hard place. Minnesota loves athletic prospects and tends to favor athleticism over polish.

Every time the Vikings select an athletic-but-raw prospect, they take a big boom-or-bust risk. In a vacuum, that risk is defensible. It just has to be executed properly. That means keeping that player out of the fire until he’s ready for NFL action. A busted defensive end can still jump into the rotation and provide some value. Because of the continuity the offensive line requires, you can’t eke out any value from a guard who isn’t good enough to start.

Unfortunately, drafted linemen who are under development become backups. If a lineman gets injured or benched, that means the backup has to go in. A ton of the line play the Vikings have endured has come at the hands of backups who aren’t ready for NFL action yet. If that player is thrown into the fire with unpolished mechanics, they’ll develop bad habits just trying to survive. Breaking those bad habits sets their development back even further.

Therein lies the risk of a boom-or-bust developmental prospect. If you’re confident that you won’t have to play that player, then hide them away in the slow cooker. But the Vikings haven’t had the luxury. If they want to prioritize athleticism over polish, that’s fine. But they have to nurture that development.

Development

The Vikings haven’t allowed their young linemen to develop in nurturing environments. Brian O’Neill and Ezra Cleveland were forced to start due to injury. Pat Elflein and Garrett Bradbury had to make the notoriously difficult NFL transition on the fly, but both players were supposed to be more pro-ready prospects, so it makes some sense for them to be Day 1 starters.

Again, on its own, this can be tenable. Offensive linemen often improve in their second or third year in the league. Just look at Kolton Miller’s development in Las Vegas. But the difference between him and the litany of failed Vikings projects is that the Raiders honed in on developing him where he was comfortable. Minnesota seems hell-bent on making it as difficult as possible for their linemen to succeed.

It’s often the result of bad luck that linemen have to start early. They had penciled Rashod Hill and Pat Elflein in as starts and planned to allow O’Neill and Cleveland to develop accordingly. With O’Neill, they probably didn’t even have to. But they add other challenges to the development of these young linemen. Chiefly, they force players into position switches far too often.

It’s hard enough to learn a new scheme in the NFL, but the Vikings love to add an extra layer. The skill sets required between guard and tackle are vastly different, and learning one when you’re used to the other is a monumental challenge. Add that to the boilerplate struggles of transitioning from a college scheme to a pro scheme, and to the NFL in general, and you’re bound to overwhelm the player. These unpolished, athletic prospects can’t be expected to succeed under these circumstances. It’s an unforced error.

Ezra Cleveland, a left tackle, spent 2020 at right guard. He had to process a college-to-pro, left-to-right, and tackle-to-guard transition all at once. The result was a catastrophic debut and overall spotty rookie campaign. The Vikings have thrown similar challenges to Pat Elflein, Mike Remmers, and countless other examples depending on how far into the past you want to go.

In a vacuum, the Vikings’ strategy seems like a smart way to pursue value. Developing athletic prospects can be a cheaper path to successful play than paying outright for their true value. But to execute this strategy, they have to be more diligent about their approach to developing that talent. As it stands now, they’re just throwing dollar bills into a foundry and hoping bricks of gold fall out.