We may have gotten one of the biggest nuggets of Minnesota Vikings draft information in an unexpected setting. Kevin O’Connell answered a football question from a fan while giving a talk that was primarily focused on faith at St. Philip the Deacon Church. In his answer, O’Connell opined on what he thinks is a fixable trait in a QB prospect, saying:

I believe the footwork and the lower half of any quarterback can be fixed with the proper coaching and teaching.

The snippet this quote came from can be seen in the tweet below, along with a link to the full video:

When unearthed, the quote predictably created a small frenzy. Desperate for any information on who the Vikings might take at QB, fans swarmed to guess who this quote might indicate the Vikings are interested in. It’s noteworthy that of the top QB prospects in the draft, Drake Maye and J.J. McCarthy are generally considered to have significant footwork issues that need to be fixed. Ted Nguyen interviewed private QB coaches with expertise in mechanics for this Athletic article, and he only mentions footwork for two — Maye and McCarthy. (For what it’s worth, the article also contains quotes suggesting the footwork issues are easy to fix.)

Footwork, which is a sub-category of QB mechanics, is often treated as a buzzword in draft analysis. Many scouting reports will identify mechanics as an issue for players that leads to inaccuracy and suggest it needs to be fixed. But if you’re a QB prospect, that doesn’t exactly help you figure out a way to improve your footwork. Proper identification of flaws and coaching can certainly help improve QB footwork, as shown by Ted’s Anthony Richardson profile before the draft last year. I’m far from a QB coach, but I wanted to go through my understanding of QB footwork and how it affects throws. Hopefully, it leaves you with a better understanding of how it impacts plays. I’m primarily going to use Kirk Cousins, one of the mechanically best QBs in the NFL, to show how it’s done.

Dropback footwork: depth and rhythm

We should start right where the QB begins a play, with his dropback. It is important for a QB to not only get consistent depth but also have appropriate timing in his delivery.

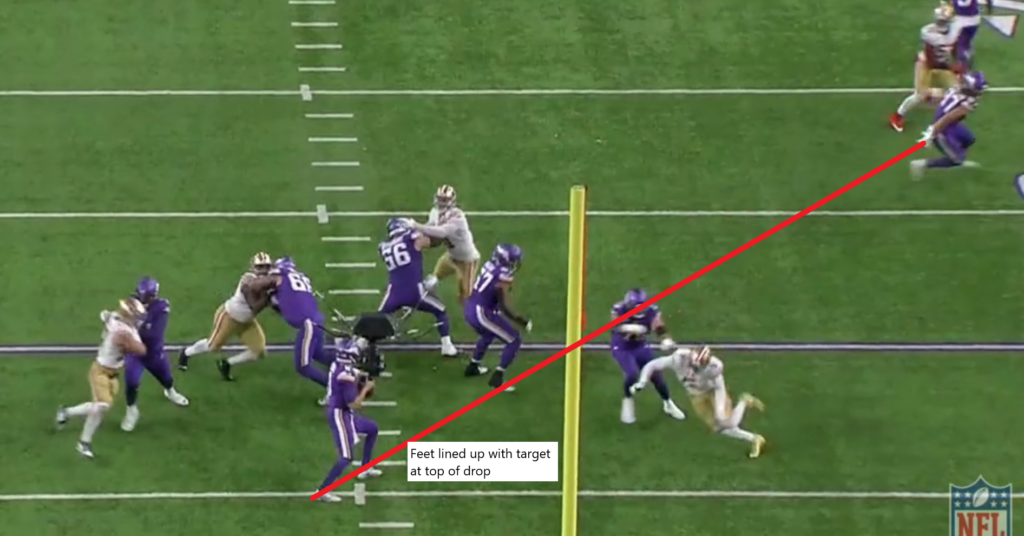

The play below is a good example of Cousins’ timing. He’s taking a three-step drop, and his first read, T.J. Hockenson, is running what I believe is an option route that functionally turns into a whip. Cousins needs to have some anticipation on this throw because Hockenson has a small window of advantage as he stops and breaks back the other way. If Cousins were late, he could have let the LB covering Hockenson back in the play.

The key for Cousins on this play is his feet. Look at how they’re aligned at the top of the drop, directly pointing at Hockenson. Once he identifies the read, he’s able to reset and throw quickly to deliver the ball on time.

In college, QBs can potentially get away with sloppy footwork at the top of their drops because the rush isn’t present or there is better spacing on the second level. However, the timing was critical for Cousins on this play. Nick Bosa was coming around the edge and nearly swiped his arm as he was releasing the ball. Had he not had good footwork at the top of his drop, he may have had to reset a second time, which could have resulted in a strip sack.

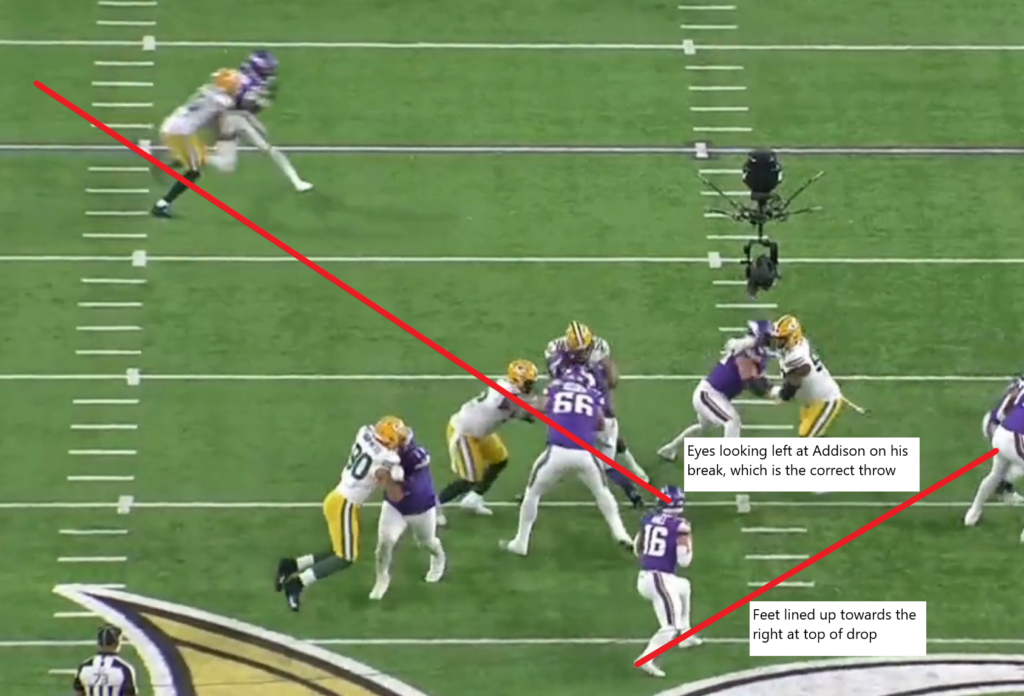

Jaren Hall provided an example of this issue in his start against the Packers. In the play below, he has Jordan Addison breaking free to the outside. However, his feet don’t align with his eyes at the top of the drop. That means he has to reset his feet once before trying to step into a throw. By the time he resets, Kenny Clark is in his face and he has to pull the ball down, taking a sack.

This is a still at the top of Hall’s drop, where his eyes are in the right place, but he can’t think about throwing because his feet aren’t lined up correctly:

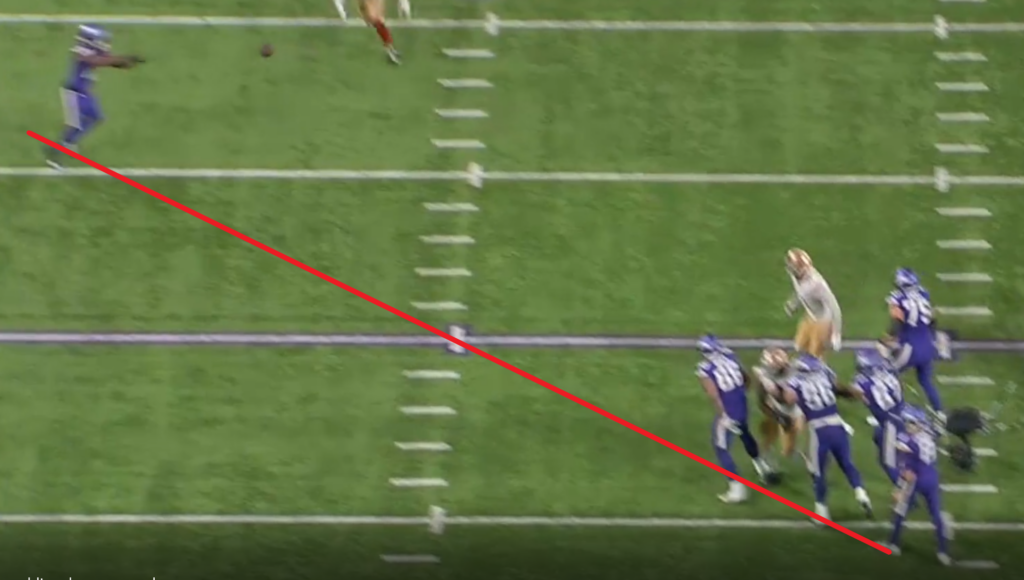

Hall resets his feet on his next step in the still below. But Clark is bearing down on him, and he must pull the ball down instead.

Depth is also critical for a QB to master in his dropbacks because it protects offensive linemen, particularly the tackles. Each dropback is designed to go to a certain depth, typically eight or nine yards. If you go beyond that, you run the risk of an edge rusher being able to turn the corner against you and hit you from behind.

Here is a good example from Cousins on a seven-step drop. The ball is snapped on the 50-yard line, and his back foot hits the top of his drop just barely behind the 41-yard line from this angle.

Contrast that with this strip sack taken by Jaren Hall. Here, the ball is snapped at the 41, and Hall drops back to just behind the 31, a full yard deeper than Cousins. Preston Smith wins the edge against Darrisaw and ends up with a strip sack.

The plays above are a bit of an apples-to-oranges comparison because the rush plan is different. However, concise footwork affects the opponent’s rush plan. Cousins has a good example of this difference against the San Francisco 49ers. In the play below, Brian O’Neill starts with a jump set. But when Bosa tries to take the edge, he has to work back to try to push him past the QB.

With the ball snapped at the 31, Bosa is trying to corner at the 22, but Cousins steps up to the 23, and Bosa has to try to rush through O’Neill to get to the QB. Juxtaposing Hall’s play above into this, Bosa would have only had to try to turn the corner at the 21, which would have been much easier for him to do and made O’Neill’s job significantly more difficult.

Drilling this footwork should be part of the process for QBs when working on plays, but it may be difficult to get down in limited reps. A young QB like Hall, who didn’t see a ton of work in the offense and lacked experience, isn’t necessarily going to have the details down like Cousins does on these plays. Time on task really matters in this case, and the Vikings will need to focus their attention on whichever QB os getting the minute details of the position right when it comes to dropbacks.

Top of drop: feet aligned with eyes and pocket movement with intent

We saw above how Cousins having his feet aligned at the top of his drop helped him throw in rhythm. That’s perfect when the first read is open, but you also have to maintain that rhythm throughout the dropback.

Watch Cousins’ feet closely on the play below. His first read is to his left, and you can see his eyes and feet both align that way. However, his read in that direction isn’t open, so he moves to his next window. You can see his helmet move to the middle of the field, and his feet line up that way too. Because his feet were lined up, he was immediately able to step into the throw and deliver a completion through contact.

Contrast that with the below play by Drake Maye. Ignoring the dropback, which isn’t really much of a dropback at all, he lands at the top of his drop with his front foot slightly to the left of his back foot, despite his eyes being all the way to the right. He then looks all the way back left before going to the middle. But every time he lands, his feet are in the same position relative to each other. Because of this lack of footwork polish, he has to try to hitch about three times before finally trying to step into the throw. By that time, it’s too late.

When moving in the pocket, it’s also critical to keep a good base underneath you, so you’re able to step into a throw at any moment. Let’s go back to the earlier Cousins play with the seven-step drop. He bounces to his left, which is intentional because of the rush in front of him. But also notice his base. His feet always stay about shoulder-width apart when he’s moving, and he also keeps his left foot forward. That allows him to step in and deliver an accurate throw that turns Hockenson away from the defender.

Contrast that with this Maye throw below. Maye is also moving to his left, but there are two critical differences. First, he lets his feet get parallel to the line of scrimmage, which will prevent him from quickly stepping into a downfield throw. He also lets his base get really narrow, almost clicking his heels together, and that leads to a massive overthrow.

Here is a side-by-side to show the difference:

Young QBs often also fail to reset their feet to throw once someone moves them off of their spot. The play below is a good example of Cousins doing just that. As he hits the top of his drop, he feels that he has to run up in the pocket rather than do a typical hitch up, because of potential pressure from the right. While he doesn’t consistently maintain a throwing base on this play, he ends up setting up before he throws. If a QB wants to be consistently accurate, it’s important to do this when you have the space:

It’s not always possible to set your feet on a play, though, and that could consistently lead to issues with a player like Cousins. It’s impressive when a player has the talent to deliver balls without a proper base, which Maye clearly does:

However, it will be important for Maye to gain a consistent base so throws like the above are reserved for special occasions rather than the scattershot accuracy he currently has.

Throwing: lined up to throw and front foot pointing at the target

I’ve written a lot in the previous sections about the importance of a quarterback’s dropback process leading to him being lined up to throw, but I want to go deeper into how that alignment affects accuracy.

Generally, you want the line between your back foot and front foot to point toward the target, but you actually want your stance to be a little open. That allows your hips to fully rotate and will leave you perpendicular to your target, like on the TD throw below from Cousins.

If your stance is too closed off, you can leave the ball behind your target. Look at the play below from Cousins. He’s throwing to a similar angle, but his front foot is further right, meaning a more closed-off stance. Along with the pressure that contacts him as he’s throwing, this prevents his hips from rotating all the way through the throw. Therefore, he leaves it a step behind, and Jordan Addison makes a spectacular play.

Take a look at the throws side-by-side. You can see the difference in Cousins’ feet, followed by the difference in hip rotation he’s able to get on each throw:

The final critical component of consistent accuracy for a passer is getting their front toe to point directly at the receiver. To get the most power on a throw, you want it to be lined up. Any extra rotation is an energy leak, and you also want to have all of your cleats in the ground to put the most force possible into the throw.

The below play from Cousins is a great example:

It’s really easy to see on this play because Cousins keeps his front foot planted in the ground long enough for the camera to pan to the receiver.

Contrast that play from Cousins with J.J. McCarthy’s throw below. McCarthy does some good things, including keeping a wider base and aligning his back and front foot towards the target. However, he doesn’t point his toes in the correct direction, and that leads to a throw behind his receiver because his hip still isn’t able to get a complete rotation on the throw:

It’s very easy to see from this still that McCarthy’s toe is pointing basically down the hashes instead of at his WR:

Private QB coaches typically work on these issues. This Anthony Richardson profile shows the work that can be done to resolve some of them.

Conclusion

Can footwork be fixed in a QB? Kevin O’Connell certainly thinks so, and the issues highlighted above when comparing players to Kirk Cousins are certainly ones that can be resolved. Whether or not they actually get fixed is a different question.

Coaches usually do not pay this much attention to detail at the college level. The same is sometimes true in the NFL, where coaches are often more focused on mental preparation and installing plays than minute technical details. Quarterbacks have to take in a ton of information. However, few teams have coaching staffs with the level of quarterback-specific experience that the Vikings do.

The Vikings’ bet, should they draft a quarterback like Maye or McCarthy, is that they will be able to teach the players what they are doing wrong. Then, the players can receive coaching and work, likely outside of the team’s facility and structured practices, to shore up their footwork issues and become consistently accurate players.