Given that J.J. McCarthy is the key to the Minnesota Vikings’ future, I wanted to examine his game in as much detail as possible. While scouting his 2023 season, I also charted every single play, looking at various factors, including down and distance, alignment information, dropback type, pressure, route concepts, throw location, play result, accuracy, and a grade for each play.

In charting McCarthy, I was able to get an overall impression of his game, and then go back to the data to see if my impressions lined up with the information I had collected. You can view my charting data for yourself in this Google Sheets Workbook.

Let’s get into some of the major takeaways from this charting.

accuracy

Being able to place the ball accurately is perhaps the most important skill a QB can have. However, even the best players are not perfect on every throw. Charting allows you to see if misses are a consistent problem or are part of the normal variance.

I came up with three levels of accuracy:

- Pinpoint, where the ball was thrown in stride, required only a slight adjustment, or he put it in a place that led the receiver away from a defender.

- Accurate, where the ball required the receiver to adjust significantly to make a catch. These throws were definitely catchable but not perfect. (Pinpoint passes are a subset of accurate passes, and thus all pinpoint passes are also included in the general “accurate” category.)

- Inaccurate, where the ball was outside of the receiver’s frame and very difficult or impossible to catch.

I charted 312 “aimed” passes; I removed tipped passes, throwaways, hit as thrown, and gadget plays like tap passes from the sample. On those aimed plays, McCarthy made 250 accurate passes (80.1%) and just 62 inaccurate passes (19.9%). Of those accurate passes, I rated 198 of them pinpoint (63.5% of the total attempts).

Trying to grade accuracy led me to realize that it’s a philosophical question in some cases. How the receiver adjusts to the ball can impact the perception of a throw. For example, look at the following play:

In the play above against Bowling Green, McCarthy throws what I believe to be an accurate ball to a receiver who adjusts poorly and drops it. In my poll (which, admittedly, is likely tainted by being responded to by people who are primarily Vikings fans), over 90% of responders said the throw was accurate. However, PFF disagrees and did not include this throw as accurate in their adjusted completion percentage.

Still, most throws are pretty straightforward despite some discrepancies on the margins. To evaluate my charting data, I compared pinpoint passing rates to data from Ben Solak’s charting at The Ringer, accuracy rates to PFF’s data on NFL QBs in 2023, and completion rates to PFF’s data for the same sample.

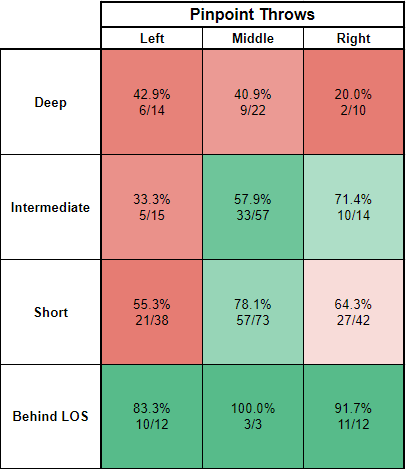

Looking at pinpoint throws, it becomes clear that McCarthy has two areas to work on: deep throws and throws to the left. Still, there are more positive signs in the data, including his throws over the intermediate middle area of the field, a location Minnesota’s offense loves to attack. McCarthy was also nearly impeccable throwing behind the line of scrimmage, including a few plays where he had to adjust his arm angle. That’s a positive sign. It gets even better when we look at general accuracy:

Stepping back to catchable passes and comparing McCarthy to NFL players leads to positive results, with 10 of the 12 squares being a shade of green. That means he was above average in that category. His ability to throw to the intermediate area of the field really shines through in this case. The NFL is notably more difficult for QBs from an accuracy perspective, but these results are impressive. Finally, let’s look at what happened from a completion perspective.

From a numbers perspective, McCarthy’s production fell a little short of his accuracy. That could indicate a receiver issue. Outside of Roman Wilson, Michigan’s receivers really struggled to provide consistent separation. With strong TEs, McCarthy outpaced the NFL over the middle of the field. Hopefully, the upgrade in receiving talent at the next level will help boost McCarthy’s accuracy in his weaker areas.

There’s an additional layer here. When I initially set out, I wanted to count plays where the throw was placed where McCarthy intended but was broken up by a DB as accurate. These plays aren’t really ball placement. Instead, they were timing/decision-making issues. For projecting accuracy moving forward, That might be a more useful way to look at it, but I don’t have great data as a comparison point. Here are the pinpoint and accurate datasets with those throws included, and you can see they help his charts significantly:

Let’s dig a little deeper into McCarthy consistently missing left on throws. I talked about accuracy being based on perception with the example above, and one thing I did not credit McCarthy for was what might be a systemic route-running issue with the Michigan receivers. Particularly on throws to the left, McCarthy regularly missed them short, with the ball being in front of them. There’s a chance — and we can’t know for sure unless we were in the Michigan room — that the receivers were running the routes at the wrong depth.

For example, take this out route in the Ohio State game. This is a first-down play, and the receiver is running an out route. The ball hits the ground at the receiver’s feet, about six yards from the line of scrimmage. The thing is, most offenses coach this route to six yards of depth. So did the receiver, who is at seven yards, drift too far in his route? If this was intended to be a low throw from McCarthy for a quick gain on first down, it could have been exactly where he intended it.

Here is an example of the out, or “stick” route in the Shanahan system, which shows it breaking at six yards:

In my scouting piece, I showcased this throw to Roman Wilson, which could have a similar root cause:

Ultimately, I decided to chart both throws and others like them as inaccurate. But it’s food for thought in terms of how we perceive accuracy.

Offensive design

Another interesting insight for the charting data is a detailed look into Michigan’s passing game. Despite a low number of overall attempts compared to other prospects, McCarthy’s tape showed very little fat. Per PFF, Bo Nix threw 111 screens. That means that over a fifth of his dropbacks don’t give you much information on who he is as a player. For McCarthy, I charted 379 plays that were passing plays from scrimmage. Of those, they had:

- 25 under-center snaps (6.6%)

- 30 pistol snaps (7.9%)

- 324 shotgun snaps (85.5%) (In 2023, 70.6% of the Vikings’ pass attempts were out of shotgun)

Obviously, this does not represent all of Michigan’s snaps because I did not include run plays. But it does show that they were willing to use pistol and under-center plays to pass, which will serve McCarthy well as he transitions to the NFL.

In addition, here are the types of play design Michigan used in that sample:

- 23 gadget plays, including flea flickers (6.1%)

- 20 screens (5.2%) (The 2023 Vikings threw screens 8% of the time per Sports Info Solutions, 29th in the NFL)

- 78 play action dropbacks (20.6%) (2023 Vikings were at 21% — second)

- 21 designed rollouts (5.5%) (2023 Vikings were at 9% — fifth)

- 61 straight play-action (no rollout) dropbacks (16.1%)

One notable takeaway for me is slightly counter to a common talking point about the Vikings. Many analysts have mentioned that Kevin O’Connell‘s rollout designs will help McCarthy as he enters the NFL. The thing is, neither O’Connell with the Vikings nor Michigan roll out nearly as frequently in college as that analysis implies. It’s also noteworthy that of Michigan’s under-center snaps, they ran straight dropback PA on 17 of them and only six rollouts. That’s also common in the O’Connell offense, where he uses play action and a deep dropback to attack the middle of the field, intermediate and deep. Having that experience should help McCarthy mesh in Minnesota’s offense.

If I eliminate rollouts and a couple of other plays where McCarthy did not traditionally drop back, McCarthy dropped back 346 total times. Of those, he had had a one-step or shorter dropback on 115 snaps, or 33.3% of plays. He mostly took standard three-step dropbacks, with 162 snaps, or 46.8% of plays, but also incorporated a significant number of “deep” dropbacks, which include elongated three-step drops and five- and seven-step dropbacks, with 69 total at 19.9% of the time. That shows good variety in McCarthy’s experience. Quick game was common, but longer-developing plays also existed.

Decision-Making and under pressure

What about the mental side of the game? The two biggest indicators for how a QB processes the game are his ability to go through reads to find the open player, and his response when pressure is bearing down on him.

In my scouting report, I noted that McCarthy had an issue where he turned down open receivers in some cases, progressing to the next read or scrambling instead. Unfortunately, I did not collect data on that issue, but it likely came out to about 5-10 plays throughout the season. Even when he did turn down opportunities, the result of the play was usually a safe completion, so it isn’t a deal-breaker for me:

However, I have data on how often he threw to certain reads based on the play design. Of 300 total dropbacks with designed reads drawn up (and no scramble), McCarthy threw:

- 182 passes to the first read (60.7%)

- 63 to the second read (21%)

- 55 to a player beyond the second read (18.3%)

That’s a decent spread. Most throws, particularly in quick game, will go to the first read on the play because pre-snap reads often determine who is going to be open. Still, McCarthy shows the ability to consistently progress beyond that first read and doesn’t get stuck waiting for a player to come open. Below is one of my favorite throws from his season. You can see him go through all four receiving options to complete a dig on the back side of the play, a popular route in Kevin O’Connell‘s offense:

McCarthy also consistently pushed the ball down the field on the plays where he had true reads. Gadget plays are going to be shorter passes and will bring the depth of target down. Therefore, eliminating them will naturally increase it. Still, McCarthy had an impressive ADoT of 11.4 on those plays and was accurate on 218 (72.7%) of those throws. Throwing further down the field also held true on third down and under pressure:

Speaking of under pressure, how did McCarthy preform in those situations? First, it’s important to look at the performance of his offensive line. I charted 373 plays where the defense had an opportunity to pressure McCarthy, and I recorded 105 pressures (28.2%) on those plays. Of those pressures, the responsibility broke down to:

- 8 on McCarthy (7.6%)

- 20 on coverage (19.0%)

- 18 on scheme (17.1%)

- 59 on OL (56.2%)

McCarthy rarely created his own pressure, and, in my opinion, Michigan’s pass blocking was very poor. PFF data shows similar results to my data:

PFF was a bit harsher in assigning pressures overall and assigned a few more pressures to McCarthy. Still, compared to the rest of the class, he was barely responsible for his own pressure.

Not all pressure opportunities are created equal, though. When the QB takes a one-step drop and releases the ball, it’s virtually impossible for the defense to create pressure, so I changed the sample to only plays where McCarthy had three-, five-, and seven-step drops. That gave me 232 dropbacks, where he faced 84 total pressures (36.2%). The responsibility broke down as:

- 7 on McCarthy (8.3%)

- 14 on coverage (16.7%)

- 8 on scheme (9.5%)

- 55 on OL (65.5%)

Overall, this is still an impressive showing for McCarthy and exposes even deeper the flaws in Michigan’s offensive line. He’s not holding on to the ball too long, but the blockers in front of him are getting beaten regularly.

Running game

Because of the way college football records statistics, where they count sacks taken as rushes, it’s hard to get a feel for a QB’s rushing ability from the box score. McCarthy’s box score reads as 64 attempts for 202 yards, at a 3.2 yards per attempt average. However, his 19 sacks for 153 yards lost bring down that average. I recorded 47 true rushing attempts for McCarthy (two plays were called back due to penalty). On those, he averaged 7.8 yards per attempt and recorded 370 total rushing yards, an impressive number. That can be broken down even further into designed runs and scrambles:

- 27 designed runs for 191 yards (7.1 yards per attempt)

- 20 scrambles for 179 yards (9 yards per attempt)

McCarthy thrived in both facets, and his mobility should be a big asset in the NFL game. Michigan wasn’t afraid to use him on designed runs with varied concepts. Of the 27 designed runs, they ran:

- 18 Zone Read (traditional “Read Option”) plays

- 3 GT Counter/Option

- 3 QB Draws

- 2 QB Sweeps

- 1 QB Sneak

Zone read is the easiest to install, but I was impressed that they were also willing to go to GT Counter in the playoff game against Alabama and run the sweeps and draws in some critical third-down situations. That shows trust not only in the QB’s athleticism but also in his ability to reach the sticks.

Of note, McCarthy only fumbled three times on the season, with two coming on sacks and the third coming on a botched snap/handoff. All QBs fumble, but McCarthy did so at a very low rate.

Other interesting tidbits

Because of my charting, I was able to calculate the true throw distance of most of McCarthy’s passes. This accounts for the extra distance he was behind the LOS and the distance it takes to throw to the left or right using the Pythagorean theorem. His longest throw was this 58-yard completion against Minnesota:

His longest “pinpoint” throw was this 53-yard dime against Purdue:

McCarthy wasn’t afraid to throw the ball to the sidelines, even to the field. He had over 10% of his attempts outside of the numbers to the field, which, on the horizontal, is 26 to 33 yards away from the opposite hash. In the NFL, those types of throws to the field are much easier and only 18 to 30 yards from the LOS because the hashes and numbers are narrower. McCarthy’s willingness to throw outside meant that if you look at the 300 “True Read” plays I described above, he was throwing the ball an average of 25 yards in the air.

In all, I charted 343 pass attempts for McCarthy, including plays negated by penalty. He completed 242 (70.5%) of those, and I recorded 17 drops by his target (PFF counted 20 drops). Those numbers weren’t boosted by quick throws. Only 27 (7.9%) of his attempts were behind the LOS, and 132 (38.5%) were over 10 yards down the field.

He only had eight passes batted or tipped (PFF recorded five, and Caleb Williams, Drake Maye, and Michael Penix all accounted for more). McCarthy only threw the ball away twice all season (PFF only counted one), which is something I would like him to work on. About half of the times he put the ball in harm’s way (I counted nine interceptable passes) were situations where he tried to hold on to the play for too long and force a throw.

The last thing I did was assign a value — positive, negative, or neutral — to every play McCarthy made. With 420 snaps recorded, I ended up with:

- 244 neutral plays (58.1%)

- 121 positive plays (28.8%)

- 55 negative plays (13.1%)

I tried to treat neutral plays as plays I would expect any QB to make or plays that were a little up-and-down. Positive plays were ones I considered impressive, while negative ones were disappointing compared to a standard QB, from easy missed throws to missed reads to catastrophes. I don’t have a standard to judge the results against. Still, positive plays outpacing negative plays at an over two-to-one rate is nice to see.

Of course, only time will tell the tale. For now, we can only speculate, but these charts provide some key indications — not to mention reason to be excited about Minnesota’s rookie QB. For more perspective on McCarthy, check out my scouting report.