The world is full of mysteries. Countless unknowns tease humanity with their concealed truths. In sports, it’s much the same. One significant question that is always on the minds of fans; will this athlete/prospect be good in the future? Predicting the future is a highly sought-after skill, though it’s impossible to master. What isn’t an unsolvable mystery? People have Negativity Bias. No matter how positive things are, we have a tendency to focus on whatever negatives exist.

Contrary to the surrounding feelings, the Minnesota Twins are doing okay. They’re hanging in the AL Central race with a 2.5-game lead. Their superstar hitters have been disappointing, a starting pitcher is hinting at retirement, and the entire AL East has a better record than the Twins. There’s no shortage of negatives surrounding this team. It would be fun to write all about the positives, but it’s even more fun to exercise another human phenomenon: Rather than focusing on the issue at hand this season, let’s turn our attention to something else entirely.

Minnesota has an exciting trio of starters who have either already excelled or have the potential to in the future. Off-season acquisition Pablo López and veterans Sonny Gray and Kenta Maeda have performed well in Minnesota, but their arsenals and skills are well-known now. Joe Ryan (27), Louie Varland (25), and Bailey Ober (28) may not be young in the literal sense, but they’ve only recently reached the majors. They are still shuffling through pitches to find what sticks. Ryan, especially, has pitched well, but his offseason additions of a splitter and sweeper tell us he hasn’t found the perfect mix. Ober is the next most accomplished, but he’s accrued just over a year of MLB service time. For today’s purposes, he’s young.

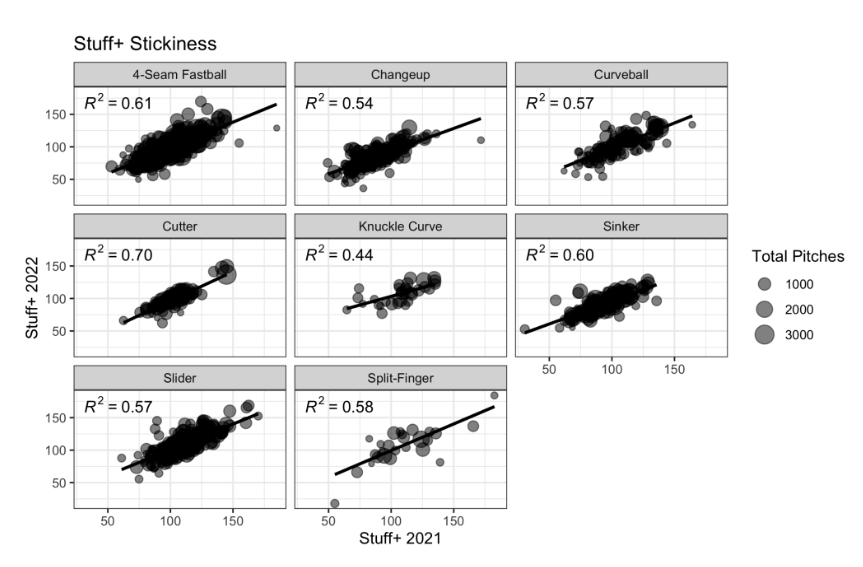

The most coveted skill in young pitchers is a good fastball. Serving as the setup to all the other pitches in an arsenal, much of the success of secondary pitches is tied to fastballs. Furthermore, fastballs are the stickiest pitch. We know this thanks to Owen McGrattan of Pitching+ (the image below is his). Fastball movement, velocity, and spin do not change much from year to year. The characteristics of other pitches, like curveballs and changeups, are more difficult to maintain.

At one point, Joe Ryan’s fastball was mysterious. Releasing it a pinch under 5 feet off the ground, his vertical approach angle (VAA) does wonders. The pitch does not grade well in Fangraph’s Stuff+ (103) due to its mediocre velocity and movement. We know the true ability of his fastball is much higher because of his VAA. Ryan will continue to have an outstanding career with such a strong base in his fastball. He’s just a couple of pitches away from being a dominant frontline starter recognized by every fanbase and therefore a likely All-Star.

The splitter he learned in the offseason could become one of those secondaries. He’s had trouble locating it, leaving far too many up in the zone. It’s normal if not desired to have some splitters fall in for strikes, but to truly get the most out of the pitch, he’ll need them more often than not to dip just below. I speculated the issues he’s had are grip-related, resulting in too much unwanted spin and therefore not enough drop. This could be part of the reason why the pitch is graded just a 92 in Stuff+.

Varland has a similarly graded fastball by Stuff+ (104) as Ryan, and he also loves to live high in the zone with it. It isn’t the most incredible fastball, but 104 is a very respectable number. If he’s able to figure out his secondaries, he should have a very nice career. The problem is that there are some issues with his changeup. Varland already features a 108 Stuff+ slider. It achieves both exceptional vertical and horizontal movement.

So much so, in fact, that the gap between the movement of his slider and the movement of his fastball may be too much. It’s not a widely accepted theory yet, but I went a little deeper in this piece on Tyler Mahle. As long as he mixes in enough cutters to prevent easy identification of his fastball and slider as they come off his hand, he’s got a solid three-pitch mix to work with.

However, his changeup is the next step. His 86 Stuff+ grade makes it his worst pitch. Movement on changeups is a relatively new focus. The deception of a changeup will likely always be its most important property. But today, changeups are a viable whiff pitch. The most substantial change Varland can make with his changeup is location. Specifically, Varland’s tendencies to “tug” his changeup, as evidenced by his 29.4% glove-side location (gLoc%). He’ll be at his best when he’s consistently throwing changeups arm side and down.

Of the three pitchers discussed, Ober has objectively the worst fastball. Stuff+ deems his fastball a paltry 72. He has a number of tricks up his sleeve that allow him to exceed expectations associated with such a low grade. The 7.5 feet of extension he throws with helps his fastball play about 2-3 mph faster than it really is. Combining that with better-than-average spin and a serious concentration of fastballs up high, Ober compiles elite numbers of whiffs.

The same extension-affected velocity boost applies to his other pitches, but none of them grade higher than 97. What does stand out about Ober is his 105 Location+. Ober has located pitches exactly where they need to be and on a regular basis. What does a pitcher do when they’ve already mastered command of their pitches? There’s no easy way to improve stuff, so adding more pitches may be the best answer and only answer.